Arctic: heat, fire and melting ice

Exceptional and prolonged heat in Siberia has fuelled devastating Arctic fires. At the same time, rapidly decreasing sea ice coverage has been reported along the Russian Arctic coast.

Exceptional and prolonged heat in Siberia has fuelled unprecedented Arctic fires, with high carbon emissions. At the same time, rapidly decreasing sea ice coverage has been reported along the Russian Arctic coast.

The northernmost inhabited Arctic town, Longyearbyen on the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard, saw a new record temperature of 21.7°C on 25 July, compared to July average of 5.9°C, according to Norway's national meteorological service.

Temperatures in Siberia have been more than 5°C above average from January to June, and in June up to 10°C above average. A temperature of 38°C was recorded in the Russian town of Verkhoyansk on 20 June. Temperatures in parts of Siberia the week beginning 19 July again topped 30°C.

The prolonged heat is related to a vast blocking pressure system and a persistent northward swing of the jet stream, allowing warm air into the region.

Nevertheless, such extreme heat would have been almost impossible without the influence of human-caused climate change, according to a rapid attribution analysis by a team of leading climate scientists.

“The Arctic is heating more than twice as fast as the global average, impacting local populations and ecosystems and with global repercussions. “What happens in the Arctic does not stay in the Arctic. Because of teleconnections, the poles influence weather and climate conditions in lower latitudes where hundreds of millions of people live,” said WMO Secretary-General Petteri Taalas.

Arctic Fires

Satellite images from Europe's Sentinel 3 showed that the wildfires currently affecting Siberia inside and outside the Arctic Circle cover a width of about 800 kilometers. The fire front of the northernmost currently active Arctic wildfire reached over the 71.6N, less than 8 kilometers from the Arctic Ocean.

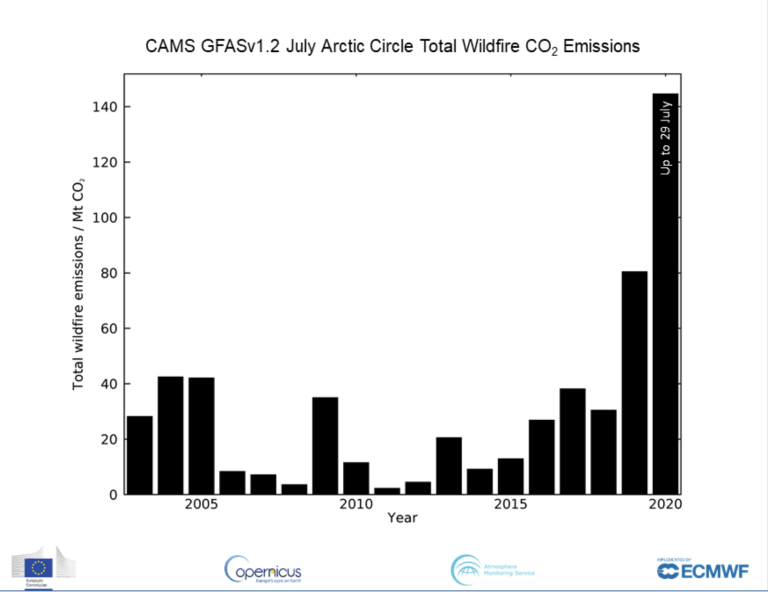

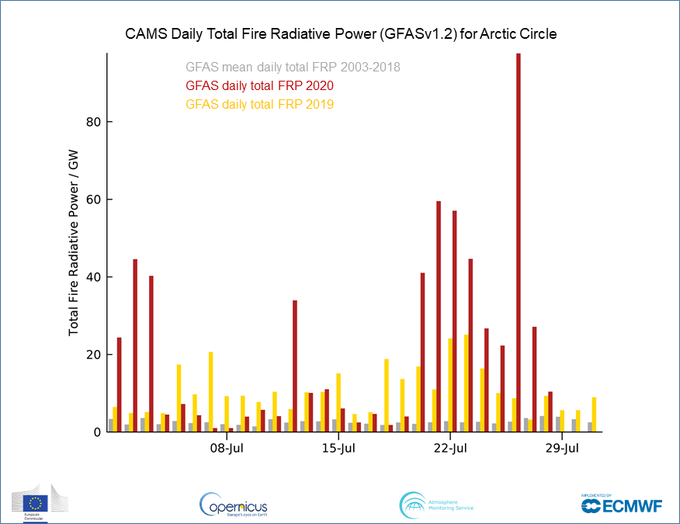

July 2020 has witnessed escalation in Arctic fires previously unseen in the EU Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service Global Fire Assimilation System data. July total estimated wildfire CO2 emissions have totally smashed the record set in 2019 and are the the highest in the 18 year-old data record of the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service, implemented by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), which is monitoring the fire activity and the resulting pollution to assess its impact on the atmosphere.

The fires have been particularly intense in Russia’s Sakha Republic and Chukotka Autonomous Okrug in the far northeast of Siberia, both of which have been experiencing much warmer-than-usual conditions over the past months. Russian authorities have also declared that there is an extreme fire hazard throughout the Khanty-Mansiysk Autonomous Okrug – Yugra which is in western Siberia.

CAMS incorporates observations of wildfires from the MODIS instruments on NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites into its Global Fire Assimilation System (GFAS) to monitor fires and estimate the pollution that they emit. The emissions estimates are then combined with ECMWF’s weather forecast system to predict how the pollution will move around the world and impact global atmospheric composition.

Wildfire smoke consists of a wide range of pollutants including carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, volatile organic compounds, and solid aerosol particles. Arctic wildfires emitted the equivalent of 56 megatonnes of carbon dioxide in June compared to 53 megatonnes in June 2019. Carbon monoxide levels over the northeast of Siberia were anomalously high over the region of the fires.

Arctic sea ice

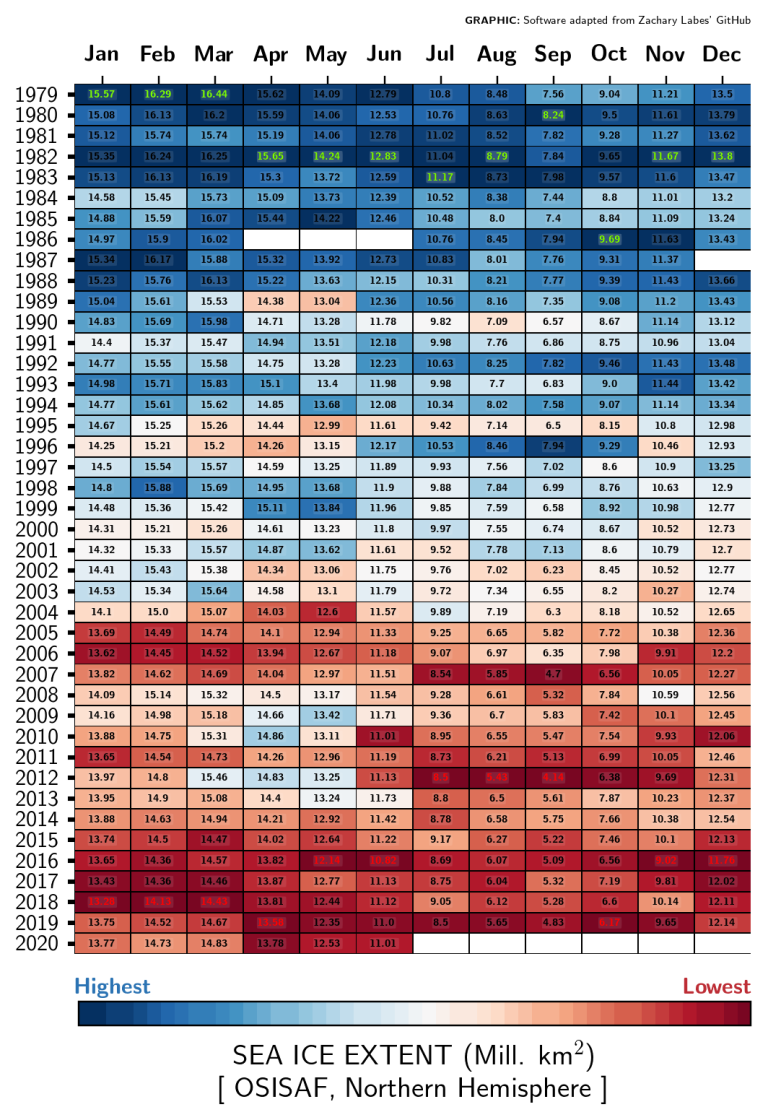

The Siberian heat wave this past spring have accelerated the ice retreat along the Arctic Russian coast, in particular since late June, leading to very low sea ice extent in the Laptev and Barents Seas, according to the available operational products of the U.S. National Snow and Ice Data Center and the US National Ice Centre (NIC). The Northern Sea route appears to be nearly open.

By contrast, the other areas of the Arctic seas appear to be near the 1981 to 2010 average for this time of year. Such contrasts serve as prominent examples of the larger variations that occur for sea ice extent on the regional scale, in comparison to the Arctic Ocean as a whole, according to NSIDC/NIC products.

There is an increasing demand for summer sea ice extent at regional scales, and with increased spatial resolution is important on a daily basis in support of

Typically, most melting occurs between July and September, when the annual minimum sea ice extent occurs. The lowest sea ice extent on record was in September 2012.

With the increased demand for higher resolution sea ice extent and thickness data, there is a need to improve the accuracy of sea ice products to make them more suitable for ice charting for maritime safety, as well as the understanding of climate driven changes at regional scales.

All datasets monitored by WMO’s Global Cryosphere Watch programme concur on the long-term downward trend in Arctic sea ice. This is believed to be affecting weather patterns in other parts of the world, and research is being conducted into whether it is leading to a weaker jet stream, which is associated with blocking patterns such as those which affected Siberia this year.

The melting of ice and thawing of permafrost – thus potentially releasing the greenhouse gas methane – is having a major impact on infrastructure and ecosystems throughout the region.

A new study published in Nature Climate Change says that polar bears – a symbol of climate change - may be nearly extinct by the end of the century because of shrinking sea ice.

“Our model captures demographic trends observed during 1979–2016, showing that recruitment and survival impact thresholds may already have been exceeded in some subpopulations. It also suggests that, with high greenhouse gas emissions, steeply declining reproduction and survival will jeopardize the persistence of all but a few high-Arctic subpopulations by 2100,” wrote the authors.

Links and information

Global Cryosphere Watch website is here

Polar Portal information on sea ice and icebergs

National Snow and Ice Data Center website is here

NSIDC time series plots are here

Copernicus Atmospheric Monitoring Service website is here

- WMO Member:

- Russian Federation ,

- Norway