Hurricane Laura hits USA

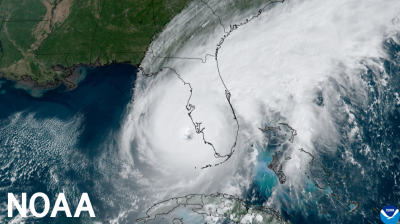

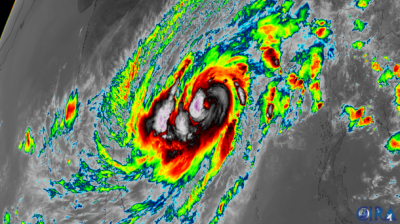

An already active Atlantic hurricane season is entering what is traditionally its most intense phase. Category 4 Hurricane Laura made landfall on 27 August on the US Gulf Coast.

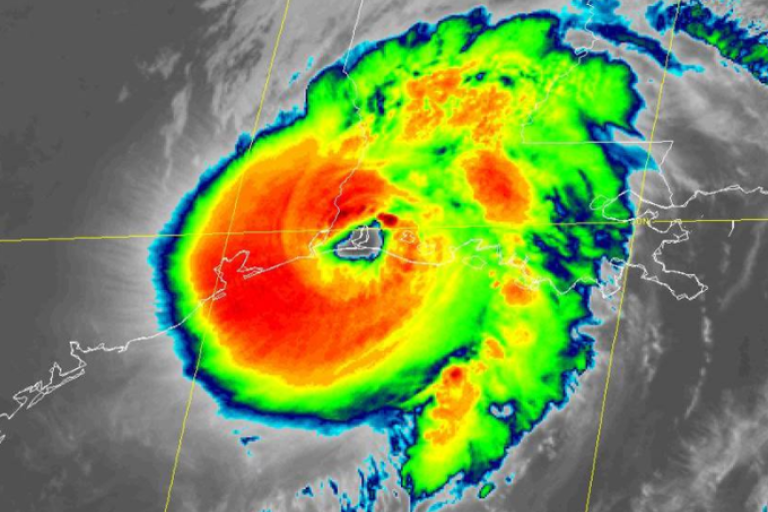

An already active Atlantic hurricane season is entering what is traditionally its most active phase. Hurricane Laura made landfall on 27 August on the U.S. Gulf Coast. It intensified within 24 hours from a category 1 to a strong category 4 on the Saffir Simson scale.

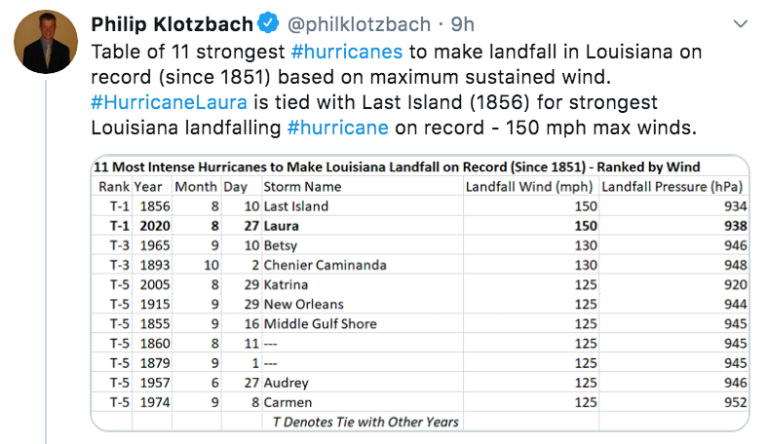

Laura made landfall in with maximum sustained winds of 150 mph (241 km/h). In terms of wind speed, it was the strongest storm (tied) to hit Louisiana

since 1856. Laura is the first major hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico during August since Harvey in 2017.

Laura has now generated more Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) than all of the other Atlantic named storms during August so far combined (Isaias, Josephine, Kyle and Marco). ACE is an integrated metric accounting for intensity and duration of storms.

It is the 7th named storm to landfall in the United States this season. It is by far the most intense and dangerous hurricane so far. We have only just entered what is traditionally the most intense period of the season. “We still have a long way to go, with climatology saying we have about 70% of strong activity in the season still left,” according to Eric Blake, senior hurricane specialist with the National Hurricane Center.

The forecasts issued by the US National Hurricane Center were extremely accurate. The accurate forecasts, together with an effective disaster management response seems to kept the death toll to a minimum, according to initial casualty reports. More than 20 people died, mostly in Haiti, when Laura was still classed as a tropical storm.

The airport at Lake Charles, Louisiana, reported a gust of 206 km/h (137 mph). The doppler radar from National Weather Service Lake Charles was destroyed – these are usually constructed to withstand winds of between 200 and 240 km/h. TV images showed many destroyed buildings in Lake Charles.

A National Ocean Service tide station at Calcasieu Pass, Louisiana observed a water level rise of 9 feet mean high water.

Active season

There have so far been 13 named storms this season.

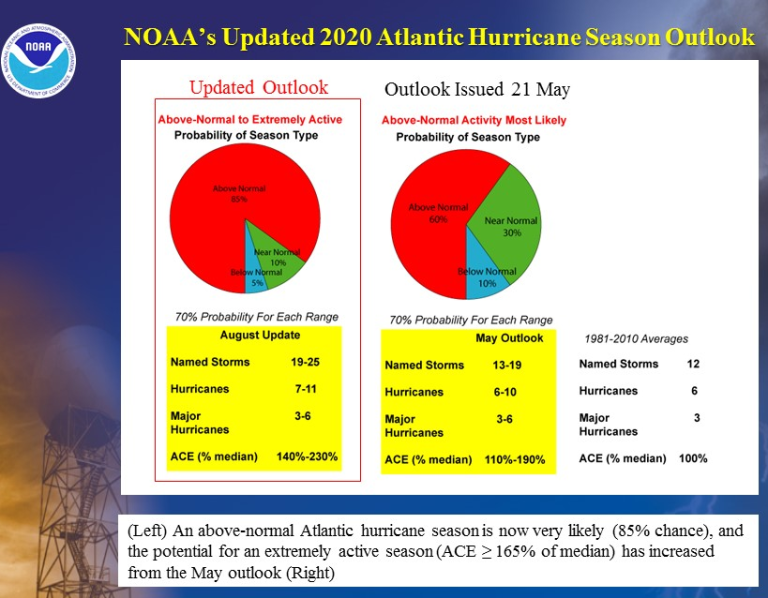

NOAA’s updated hurricane season outlook issued on 6 August indicates that an above-normal hurricane season is very likely, and there is an increased possibility of the season being extremely active, with 19-25 named storms, including 7-11 hurricanes and 3-6 major hurricanes (category 3 and above). This is because of conducive atmospheric and oceanic conditions in the part of the Atlantic where tropical storms develop, such as well above average sea surface temperatures, weaker trade winds, weaker windshear and a strong west African monsoon.

WMO’s newly issued El Niño/La Niña Update says there is a 60 % chance of a La Niña forming between September and November 2020. The absence of an El Niño – which tends to suppress hurricane activity – therefore does play a role. But it is not the only factor.

Emergency preparations and management are being complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The situation in the Gulf coast area stands in contrast to the raging wildfires in the West coast which have destroyed more than 1 million acres (more than 400,000 hectares) and claimed a number of lives. The US National Weather Service is warning of the risk of more dry thunderstorms which bring little rain but pose an additional fire threat.

Relationship with Climate Change

It is difficult to link any particular individual tropical cyclone to climate change. But we do expect to see more powerful storms in future as a result of global warming. That's because storms feed on warm water, and higher water temperatures also lead to sea-level rise, which in turn increases the risk of flooding during high tides and in the event of storm surges. Warmer air also holds more atmospheric water vapor, which enables tropical storms to strengthen and unleash more precipitation.

A summary statement issued in 2018 by Tom Knutson, Chair, WMO Task Team on Tropical Cyclones and Climate Change, said:

"The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Fifth Assessment Report presents a strong body of scientific evidence that most of the global warming observed over the past half century is very likely due to human-caused greenhouse gas emissions. But what does this change mean for hurricane activity? Here, we address these questions, starting with those conclusions where we have relatively more confidence:

Sea level rise–which very likely has a substantial human contribution to the global mean observed rise according to IPCC AR5--could be causing higher storm surge levels for tropical cyclones that do occur, all else assumed equal.

Tropical cyclone rainfall rates will likely increase in the future due to anthropogenic warming and accompanying increase in atmospheric moisture content. Models project an increase on the order of 10-15% for rainfall rates averaged within about 100 km of the storm for a 2 degree Celsius global warming scenario.

Tropical cyclone intensities globally will likely increase on average (by 1 to 10% according to model projections for a 2 degree Celsius global warming). This change would imply an even larger percentage increase in the destructive potential per storm, assuming no reduction in storm size. Storm size responses to anthropogenic warming are uncertain.

The global proportion of tropical cyclones that reach very intense (Category 4 and 5) levels will likely increase due to anthropogenic warming over the next century. There is less confidence in future projections of the global number of Category 4 and 5 storms, since most modeling studies project a decrease (or little change) in the global frequency of all tropical cyclones combined.

- WMO Member:

- United States of America ,

- Haiti ,

- Dominican Republic ,

- Cuba ,

- Japan ,

- Republic of Korea ,

- Democratic People's Republic of Korea ,

- China